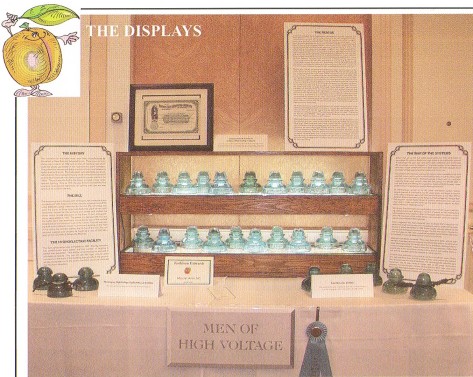

Men of High Voltage - Elihu Thomson, Edwin Houston & Thomas Edison

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", September 2001, page 5

Display by:

Kathleen Edwards

1726 Rogers Road, Mt. Airy, NC 27030

336-351-4850 gladsome@usa.net

Winner:

1st Place N.I.A. General

Milholland Education Award

Best use of

Eastern Glass

(CRABSInc.) - Pictured

Best First Time Display (CFIC)

Best use of

Power (GCIC)

Elihu Thomson

Born March 29, 1853 - Manchester, England

Died March 13, 1937 - Swampscott, MA

"There is scarcely a day passing on which some new use for electricity

is not discovered. It seems destined to become at some future time the means of

obtaining light, heat, and mechanical force," wrote high school student

Elihu Thomson. He was predicting the future of the electric sciences and his

calling as one of America's most prolific inventors.

Elihu Thomson was an

electrical engineer and inventor whose discoveries in the field of alternating

current phenomena led to the development of successful alternating-current

motors. He was also one of the primary founders of the U.S. electrical industry.

From modest beginnings with fellow high school science professor Edwin Houston,

Thomson built one of the leading electrical companies of the nineteenth century.

His experiments with alternating current, although disputed as dangerous by

direct current promoter Thomas Edison, led to the adoption of alternating

current technology as the U.S. standard. Six months before Thomas Edison opened

his first power station in New York, Elihu Thomson's system was lighting streets

in Kansas City, Missouri.

Thomson left England for Philadelphia as a child and

later taught chemistry and mechanics at the Central High School there. With a

fellow teacher, Edwin J. Houston, he designed an arc lighting system that attracted financial backing

and led to the founding (1880) of the American Electric Company in New Britain,

Connecticut, of which Thomson held 30 percent of the stock and was chief

electrical engineer. In 1882 a group from Lynn, Massachusetts bought controlling

interest in the company and moved it to Lynn. Thomson went to Lynn with the

company, which in 1883 was renamed the Thomson-Houston Electric Company, and

remained there as a consultant to the General Electric Company, which was formed

in 1892 by the merger of Thomson-Houston with the Edison General Electric Company.

In addition to his alternating-current

motor, Thomson invented the high-frequency generator (1890), the high-frequency

transformer, the three coil generator, electric welding by the incandescent

method, and the watt-hour meter. Thomson also did important work in radiology,

improving X-ray tubes and pioneering in making stereoscopic X-ray pictures. He

was the first to suggest the provision of a mixture of helium and oxygen for

workers in caissons and tunnel borings to prevent caisson disease (bends). He

held some 700 patents and received many awards.

Edwin James Houston

Born July 9,1847 - Alexandria, VA

Died March 1,1914 -

Philadelphia, PA

Edwin J. Houston was an electrical engineer who heavily

influenced the development of commercial lighting in the United States.

A

Philadelphia high school teacher, Houston collaborated with Elihu Thomson in

experimenting on induction coils, dynamos, wireless transmission, and the design

of an arc lighting system (patented in 1881) that was widely successful and led

to further improvements in lighting techniques. The Thomson-Houston Electric

Company organized in 1883 at Lynn, Massachusetts, merged with Thomas Edison's

company to form the General Electric Company. In 1893 Houston was appointed

chief electrician at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where he

implemented George Westinghouse's two-phase alternating-current power system.

Thomas Alva Edison's Life

|

1847

|

Thomas Alva Edison was born in Milan, Ohio, to

Samuel and Nancy Elliott Edison.

|

|

1854

|

Family moved to Port Huron, Michigan.

|

|

1855

|

Attended school for three months.

|

|

1859

|

Began selling newspapers, candy and food

on the Grand Trunk Railway between Port Huron and Detroit.

|

|

1863

|

Employed as a

telegraph operator traveling through the South and Midwest.

|

|

1869

|

Patented his

first invention -- the Electrical Vote Recorder. Moved to New York City. Started

a business manufacturing telegraph equipment. Invented the Universal Stock

Ticker. Opened first factory and lab in Newark, NJ. Married Mary Stillwell.

Received a patent for paper ticker tape.

|

|

1874

|

Developed a quadraplex system

which changed the telegraph industry.

|

|

1876

|

Established a laboratory at Menlo

Park, New Jersey. Received patents for the mimeograph machine and electric pen.

|

|

1877

|

Invented a carbon button transmitter for use in the telephone. Invented the

phonograph, which he believed to be his most original invention.

|

|

1878

|

Founded

the Edison Electric Light Company.

|

Unused Stock Certificate of Edison Illuminating Company.

This is the company

that constructed Hydroelectric Plant from

which ran the first long-distance,

overhead power line in the

country. It was only three miles long and was

insulated with the Thomson-Houston CD 245.

|

1879

|

Invented the first practical incandescent electric light bulb.

Demonstrated it to the public by lighting Christie Street on December 31st.

|

|

1880

|

Discovered the Edison Effect which would become the foundation of the field of

electronics.

|

|

1881

|

Began mass production of light bulbs and electric parts.

|

|

1882

|

Established the Pearl Street Central Power Station in New York, the first

commercial electric power plant.

|

|

1883

|

Edison Illuminating Company began building

municipal power plants.

|

|

1884

|

Edison's wife, Mary Stillwell, died at age 29.

|

|

1885

|

Received first patents on wireless telegraphy.

|

|

1886

|

Married Mina Miller.

|

|

1889

|

Consolidated many of his separate companies into the Edison General Electric

Company. Invented the kinetograph, forerunner of today's motion picture camera.

|

|

1892

|

Edison General Electric Company merged with Thomson-Houston Company to

become the General Electric Company.

|

|

1894

|

Introduced the Kinetoscope to the

public by hosting the first commercial showing of a motion picture.

|

|

1896

|

Invented the fluoroscope but decided not to patent it because of its tremendous

usefulness in medicine.

|

|

1900

|

Invented the nickel-iron-alkaline storage battery.

Began construction of the Edison Cement Plant.

|

|

1902

|

Made improvements in cement

so that it could be used in major construction.

|

|

1909

|

Perfected the

nickel-iron-alkaline storage battery.

|

|

1911

|

Formed Thomas A. Edison, Inc.

|

|

1912

|

Produced the first talking motion picture.

|

|

1915

|

Named President of the Naval

Consulting Board. Produced several military-related inventions during World War

I.

|

|

1928

|

Received the U.S. Congressional Medal of Honor for career achievements.

|

|

1929

|

October 21st, reenacted the invention of the incandescent light bulb to

celebrate its 50th anniversary.

|

|

1931

|

Died on October 18th at age 84.

|

(Information compiled by Kathleen Edwards and printed in display handout, Men of

High Voltage.)

The History

The insulators on this table were, more likely, manufactured by Brookfield in

New York and delivered by rail. There is an old train station very close to an

1882 mill on a South Carolina river which used the power generated at the

hydroelectric plant upstream. The power line we rescued these insulators from

runs between a hydro plant and a mill. The hydro plant was reportedly

constructed by Edison Illuminating Company which is known to have built several

municipal and manufacturing industry power plants in the 1890s. The mill was the

first in the nation to install indoor incandescent lighting. Prior to 1879, the

year Edison invented the first practical incandescent light bulb, all lighting

used gas and was practical for outdoor use only.

The Mill

The enormous brick complex with its elegant, tall smokestack was completed in

1882. Since one of the investors supplied most of the initial $400,000 capital

investment for the mill, the mill village was given his name. In those days,

manufacturing plant owners built residential homes for the workers and owned and staffed

the sores which carried provisions in the town. A dam and powerhouse were added

in 1895. The power line between the mill and the hydro plant was eventually

connected to one of the earliest long-distance transmissions lines in the

nation. This mill was also the first in the nation to install incandescent

lighting. To the right of the mill is the old train station, the live line of

the mill.

The Hydroelectric Facility

The dam construction was completed in 1881.

Shortly thereafter, two powerhouses were added and the number of facilities it

served was expanded. This edifice is tremendous in size and in architectural

beauty. You can still see the huge, circular glass insulators in the walls of

the building through which the generated electricity was run to the power line

from which we collected the Thomson-Houstons.

The Rescue

In a sweet, secluded, South Carolina town, we started our day with

breakfast at a local restaurant. I found myself in the company of the most

delightful hunting companions imaginable: Ed, Larry and Doug. We were there to

collect insulators from a long-abandoned line that ran through the center of a

small town. I first heard about the existence of the line from my brother in

California who had heard about it from a South Carolina collector. I had made

two trips to the town in the spring and summer of 2000 to locate, map and count

the insulators, but had no way of getting them down from the poles. In March,

2001, I was notified by my brother that a collector friend of his in North

Carolina, with help from a lineman, had succeeded in rescuing several

Thomson-Houston CD 245s from the poles and that there were more to be recovered

in a second planned trip.

I got a call from Doug on April 3 that the second

rescue would take place on April 5 and 6. I drove to South Carolina. Thursday

night, the four of us looked over the spectacular Thomson-Houstons that had been

recovered that evening and stayed up late swapping stories and sharing photos.

Early Friday morning we were assembled and ready to undertake the rescue of all

remaining pieces. All of the insulators in this exhibit were recovered on April

5, 2001, unscrewed directly from their pins.

Shortly after 7:00 a.m., we arrived

at the first pole, laden with the objects of our desire. Ed put on his climbing

gear, and up he went. We watched with anticipation as he unscrewed the first of

many CD 245 Thomson-Houstons we would take home that day. To my complete horror,

he casually tossed each unscrewed jewel to the ground. Amazingly the rescued

pieces sustained the falls without any damage! We lifted the jewels one by one

from the pillow ground and held each to the sky momentarily for discreet

inspection.

Using a lineman's bucket, we carried six to eight insulators at a

time to the waiting vehicles and put the glass into boxes. As we filled each box

-- cell by corrugated cell -- our excitement grew. At times, we could hardly

make up boxes fast enough. Never before had I seen so many insulators on one

pole at one time. The insulators were stacked three and four crossarms high, and

some poles had double crossarms. Ed handled the most difficult job with the

efficiency of a seasoned lineman, skillfully maneuvering over the annoying

impediments he encountered as he ascended several poles --- low mounted spools,

telephone lines, trees, vines, birdhouses and protruding nails. The poles, over

a hundred years old, swayed slightly as Ed worked from one end of the crossarms

to the other. He said the wood was so hard that his hooks would barely dig in on

some poles.

We slowly wended our way through the quaint, old streets lined with

phlox, tulips, daffodils, pansies and hyacinth in full bloom. The day was comfortably warm

and overcast. Merriment was the tone of the day. With each pole picked clean,

the excitement continued to grow. "This next pole will have a mint

one!" "The one on the top left looks GREEN!" Bets were levied,

binoculars were passed around anxiously. Neighbors looked on with concern.

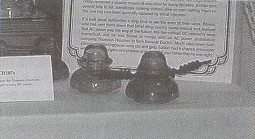

F.M. Lockes (CD 287) rescued from the same

crossarms as the Thomson-Houstons.

Note the

large gauge of wire used to carry CD current.

After

seven hours, my tiny car held all the boxes it could, so we placed the overflow

into Larry's truck. Later we returned to the hotel and sorted the booty atop

Doug's car. Hood, trunk and car top were covered with the most amazing

collection of CD 245s any of us will probably ever see. In addition to the CD

245 Thomson-Houstons, we found Hemingray CD 280s and F. M. Locke CD 287s. Some

of the Thomson-Houstons had the T-H and 9200 embossing and some, far fewer, had

the 9200-only embossing. The cable groove was not in use on any of the insulators

we recovered. At some earlier time, someone had salvaged all the copper wire

from the line using a screwdriver to pry the tie wire over the lip of each

insulator. It was an honor and privilege to be included in this hunt and a

pleasure to get to know Ed, Larry and Doug.

The War of the Systems

Edison had set up the first public power grids, but

they were based on low-voltage DC, which suffered from high losses in the

distribution network. A low-voltage DC grid was necessarily both inefficient and

short-range. AC, in contrast, could be "stepped up" to a high voltage

by the transformer, sent over a longer network with much lower losses, and then

"stepped down" to a lower voltage again by another transformer for end

use.

The problem with AC power was that all electric motors available at the

time were DC motors, and so as far as Westinghouse was concerned, Tesla might

have been sent from heaven. Westinghouse got in touch with him, and after

inspecting Tesla's work, struck a deal with him, giving him $60,000 USD in cash

and stock and offering him a generous royalty of $2.50 for every horsepower of

motor or generating capacity Westinghouse sold.

As Westinghouse worked on his AC

power distribution system, Edison became alarmed at the threat to his DC power

grids, and began a massive public smear campaign against AC that became known as

the "War of the Systems". Edison hammered on the dangers of

high-voltage AC, hiring a New York engineer named Harold Brown to publicly

electrocute stray cats and dogs. Just to make sure the public got the point,

Edison referred to these electric killings as "Westinghousing."

At the

time, New York State was investigating more humane ways of performing capital

punishment. Although a number of people on the investigating board preferred

lethal injection, which in hindsight seems the obvious choice given the

objectives of the board, Edison was consulted, and saw a perfect opportunity to

blackball Westinghouse.

Edison suggested that high-voltage AC was so deadly that

it would be the perfect way to perform an execution. His authority was so great

that the board decided to adopt the method in 1888. Brown quietly acquired patents on the necessary technology

and provided the gear. The first execution in the electric chair took place in

1890, with a convicted murdered named William Kemmler put to death. It required

several jolts of electricity to kill him.

Westinghouse bitterly remarked:

"They could have done better with an axe." He had to have been

relieved, however, that Edison had failed in his attempt to make "Westinghousing"

the formal name for the procedure. Although electrocution remained a popular

means of execution for many decades, it often took several jolts to kill,

sometimes cooking victims alive or even setting them on fire, and has not been

generally replaced by lethal injection.

It took penal authorities a long time

to see the error of their ways, Edison, who had sent them down that blind alley,

quickly came around and realized that AD power was the way of the future. His

low-voltage DC networks were impractical, and he was forced to merge with an AC

power distribution company, Thomson-Houston, to form General Electric. Much

later, when both Edison and Westinghouse were old and gray, Edison had a chance

encounter with one of the Westinghouse children and said: "Tell your father

that he was right."

(Information compiled by Kathleen Edwards to enhance

the presentation of display. Read later in this report of the amazing

"walk-in" to the show that completes the rest of the story.)

Men of High Voltage by Kathleen Edwards

1st Place N.I.A. General; Milholland Education Award; Best use of Eastern Glass

(CRABSInc.); Best First Time Display (CFIC); Best use of Power (GCIC)

|